Divisions

US Marines with 1st Light Armored Reconnaissance Detachment, Battalion Landing Team 3rd Battalion, 1st Marine Regiment, 15th Marine Expeditionary Unit, fire their weapons on the flight deck aboard the USS Anchorage (LPD 23) in the Pacific Ocean, Nov. 28. www.flickr.com/photos/15thmeu/. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Sgt. Steve H. Lopez/Released)

26 February 2016 - The Center for Adaptation and Innovation at the Potomac Institute for Policy Studies, as part of its Returning Commander Speaker Series, hosted a commander of the Essex ARG/15th MEU. This ARG/MEU completed a seven month (218 day) deployment on 15 December 2015. The deployment was divided into 38 aggregated days, 180 split days, and 18 disaggregated days.

The Marine Expeditionary Unit (MEU) is a flexible and capable standing Marine Air-Ground Task Force (MAGTF). The MEU is specifically designed to serve as globally responsive expeditionary quick reaction force, deployed aboard Amphibious Ready Group (ARG) shipping and prepared for immediate response to any crisis, to include natural disasters, theater security cooperation, and expeditionary combat missions. The ARG/MEU are becoming the operational “first choice,” and provide access and placement around the globe, including support to US embassies. Today, the ARG/MEU remains one of the most relevant forces to shape and respond to today’s security challenges.

During its deployment, which began 11 May 2015, the MEU conducted a range of naval expeditionary operations and activities in support of CENTCOM, AFRICOM, and PACOM requirements. The Pre-Deployment Training Program (PTP) focuses on integration of the US Navy (USN) and Marine Corps (USMC) into a truly naval force. Although operating as a split force for 180 days of the ARG/MEU deployment, success of their missions were attributed to training as an integrated naval force. The time spent training with special operations forces elements and informed loading of the ships – in order to increase flexibility and timeliness of response – also contributed to the deployment’s success.

While the Essex ARG/15th MEU deployment accomplished all assigned missions and tasks, some operational challenges still remain. Many of the challenges revolve around communication and overcoming the “last tactical mile.” The Navy and Marine Corps currently have a limited high frequency (HF) data capability. The USN and USMC need a digital wide band HF capability or other solution for the potential A2/AD environment. The unit is also looking for ways to close the intelligence gap from ship to shooter. The ARG/MEU needs all source intelligence capabilities at all levels as well as C5I systems that are responsive to operational demands. Other challenges, however, are of a more organization and education nature. There is a need for increased education among the naval forces and special operations forces about what an ARG/MEU can do in supporting-supported roles. Another challenge is staffing the COCOMs with enough experienced Liaison Officers with naval experience. Addressing these challenges will help better integrate the joint and allied naval force, which enable power projection and sea control across the full range of military operations.

The Center for Adaptation and Innovation (CAI) at the Potomac Institute was created to identify and define new and potentially disruptive defense capabilities. Specifically, CAI was established to assist senior defense leaders grappling with the most demanding issues and problems posed by a complex and uncertain security environment. CAI’s Returning Commander Speaker Series offers a forum for naval force concepts and capabilities to be discussed with commanders whom recently completed a deployment.

Naval Maneuver Warfare

Linking Sea Control and Power Projection

August 25, 2015

Gen Al Gray, USMC (Ret.)

LtGen George J. Flynn, USMC (Ret.)

The recent update of A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower: Forward, Engaged, Ready1 (CS-21R [Revised]) advances the understanding of the roles of all elements of the naval force in maintaining freedom of action and achieving operational access. Most importantly, it provides impetus to advance the understanding of maneuver warfare at sea. To fully exploit this opportunity, a new integrated Naval Operating Concept (NOC) is required to define and hone the linkage between sea control and power projection. An updated NOC would refine and link the operational and tactical level concepts needed to fully capitalize on all the capabilities existing within our Nation’s naval forces — to include the wide range and various roles of amphibious forces — within a naval campaign construct.

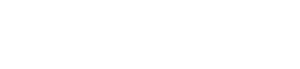

The development of operational concepts that connect strategy and tactics is not an easy task. Accordingly, it is not surprising that a gap exists today. Regardless of its cause, there is a need for the naval services to seize the moment and develop operational concepts that define the relationship between sea control and power projection in the execution of a naval campaign. This effort cannot be done independently; it must be a naval effort that is collaborative and focused on warfighting at the operational level. Fortunately, recent history provides an example of an effort that worked to successfully link ends, ways, and means. During the Cold War, The Maritime Strategy and the Marine Corps’ Amphibious Strategy2 were jointly developed, integrated efforts that drove the development of naval operational and tactical concepts and capabilities needed to achieve strategic ends. These efforts were successful because they provided the operational foundation to incorporate all naval warfare functions and capabilities into an integrated campaign plan construct. Diagram 1 shows the development of amphibious capabilities to illustrate this linkage:

Diagram 1: 1980s Concept to Capabilities

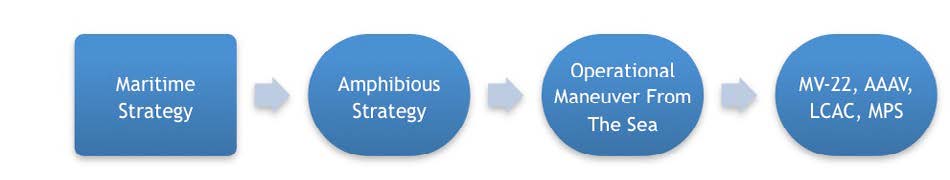

Diagram 2 illustrates the current gap between strategic concepts and the operational and tactical ability to achieve them. Additionally, this diagram highlights the challenges in executing and linking tactical level concepts to the achievement of strategic ends absent an operating concept. Air Sea Battle and Expeditionary Force 21 (EF-21) provide an explanation of actions that can be done at the tactical level, but absent a connecting operational concept, it is difficult to link these with the achievement of strategic ends. A new NOC is clearly needed to serve as the integrating document for all naval warfighting functions within a Joint Operational context. We need an NOC to drive integration of our naval air warfare, surface warfare, undersea warfare and amphibious warfare capability development.

Diagram 2: Current Concept to Capabilities Gap

Accordingly, the purposes of this paper are to articulate the need for the development of an updated NOC, define the linkage between sea control and power projection in the execution of a naval campaign, and start a discussion about the various roles of amphibious forces in a naval campaign that use the sea for operational maneuver to execute both sea control and power projection operations.

The Roles of Amphibious Forces in Joint and Naval Campaigns

Amphibious forces provide the naval capabilities needed to support and execute sea control and power projection operations in order to create area access, enable and maintain freedom of action for the Joint force across the Range of Military Operations (ROMO), and deny the enemy freedom of action and access to the global commons. Recent operations demonstrate the utility of amphibious ships embarked with Marines for day-to-day presence and crisis response operations.3 Equally as important, but less understood, are the variety of roles amphibious forces can execute while operating as part of Joint and Combined Naval Task forces in response to major theater contingency operations. Too often, amphibious capabilities in these types of operations are only associated with assaulting defended beaches and seizing lodgments for land campaigns. Focus on this singular aspect of a naval campaign is myopic, and overlooks significant capabilities of amphibious forces that can be employed in support of sea control operations and all phases of Joint access operations. Accordingly, it is also important to develop an understanding about the variety of roles that amphibious forces possess in shaping the environment, deterring aggression and defeating an adversary across all five phases of a major theater contingency campaign. A new NOC could assist in developing this understanding.

The Maritime Strategy4 of 1984 articulated a naval campaign that used the seas to conduct operational maneuver in order to seize the initiative and take the fight to the enemy.5 It provided the strategic and operational foundation for the employment of naval forces in a global conflict, and spurred the development of new tactical concepts and capabilities.6 The Maritime Strategy also articulated a naval campaign of three phases: Deterrence; Seize the Initiative; Carry the Fight to the Enemy. An indispensable element of the Maritime Strategy was the Amphibious Warfare Strategy, approved by the Chief of Naval Operations and Commandant of the Marine Corps. This strategy outlined the employment of the Navy-Marine Corps team in executing the Maritime Strategy. The Amphibious Warfare Strategy drove supporting concepts such as Operational Maneuver from the Sea (OMFTS) and Ship to Objective Maneuver (STOM), and laid the foundations for capability innovation like Maritime Prepositioning Ships (MPS), the MV-22 Osprey, and the Landing Craft Air Cushion (LCAC). These two documents also articulated a clear understanding of the use of the seas for operational maneuver, the linkage between sea control and power projection, and the various roles of all elements of the naval force.

A Fresh Approach Informed by the Past

The current Joint Operational Access Concept (JOAC) and the recently published CS-21R tie sea control and power projection together. Just as was the case in 1984, the Navy and Marine Corps must take the next step to develop the operating concepts necessary to further define their relationship and to close the gap between the desired ends and available means. In order to close this gap, naval leaders should also take advantage of emerging efforts like ones below to inform thinking and wargaming efforts needed to develop the operating concepts that are lacking. Some of the emerging efforts that can be used to inform the development of innovative, affordable, and effective operational concepts include:

“archipelagic defense” to deny a near peer competitor the ability to control the air and sea;7

development of land-based sea denial capabilities;

integration of distributed land and sea forces to deny air and sea lines of communication;

“distributed lethality;”8

the Joint Concept for Access and Maneuver in the Global Commons (JAM-GC).9

Operational Art Revisited

Along with the ongoing efforts to develop new concepts both inside and outside DoD, CS21R provides an opportunity to refine operational thinking so as to the achieve access and freedom of action required to attain strategic ends. The recent decision to incorporate the Air-Sea Battle Concept into JAM-GC underscores the need to develop a Naval Campaign construct to support the overarching Joint concept. Air Sea Battle and Expeditionary Force 21 focus on “programmatics,” and fall short of providing the operational context or approach for the employment of tactical level capabilities in a naval campaign that is part of a larger Joint effort. Again, a more viable methodology is for the Navy and Marine Corps to develop an updated NOC that outlines a cohesive operational rationale, unity of effort, and command and control construct for linking sea control and power projection operations. In turn, this would inform the development of the JAM-GC, as well as support and enable service-level capabilities, doctrine and associated tactics, techniques, and procedures.

Conclusion

As in the past, we cannot afford to allow our approach to naval missions to remain fixed in an era of changing conditions. Those conditions now demand a new NOC to define the relationship between power projection and sea control in the execution of a naval campaign within a joint and combined campaign construct across the ROMO. It must also articulate the relevance of amphibious forces in all contingencies up to, and including, major combat operations. Once naval leaders agree on the need for a new NOC, the key to success will be ensuring that the Navy and Marine Corps are joined together in leadership, doctrine and concept, operational, programmatic, education, and wargaming to make this operating concept a warfighting reality. This was the key to success in 1984, as it will be to success in the future.

Notes

1.“Document: A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower 2015 Revision,” USNI, 15 March 2015, available at: http://news.usni.org/2015/03/13/document-u-s-cooperative-strategy-for-21st-century-seapower-2015-revision.

2.John B. Hattendorf and Peter M. Swartz, “U.S. Naval Strategy in the 1980s: Selected Documents,” Naval War College Newport Papers, December 2008, pg. 203-258, available at: http://fas.org/irp/doddir/navy/strategy1980s.pdf

3.For instance, from 1990 to 2013 there were 123 amphibious operations, including doctrinal types (assaults, withdrawals, demonstrations, raids, and other operations in a permissive, uncertain, or hostile environment) and non-doctrinal types (maritime interdiction operations (MIO), mine counter-measures (MCM), and strike operations). Source: The Center for Emerging Threats and Opportunities (CETO).

4.The Maritime Strategy (Annapolis, MD U.S. Naval Institute, January 1986), pp. 2-17.

5. John B. Hattendorf and Peter M. Swartz, “U.S. Naval Strategy in the 1980s: Selected Documents,” Naval War College Newport Papers, December 2008, pg. 203-258, available at: http://fas.org/irp/doddir/navy/strategy1980s.pdf

6. The Amphibious Warfare Strategy.

7. Andrew F. Krepinevich, Jr., How to Deter China: The Case for Archipelagic Defense, Foreign Affairs, March/April 2015, available at: http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/143031/andrew-f-krepinevich-jr/how-to-deter-china

8. Benjamin Jensen, “Distributed Maritime Operations: Back to the Future?”, War on the Rocks, 9 April 2015, available at: http://warontherocks.com/2015/04/distributed-maritime-operations-an-emerging-paradigm/?singlepage=1

9. “Document: Air Sea Battle Name Change Memo,” USNI, 20 January 2015, available at: http://news.usni.org/2015/01/20/document-air-sea-battle-name-change-memo

14 January 2015

14 January 2015

1500 - 1600

Brigadier General Daniel Yoo recently served as the Commanding General of the Marine Expeditionary Brigade - Afghanistan, which deployed in the spring of 2014 in support of Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF). He was the last Marine leader to command the International Security Force's Regional Command-Southwest. Upon taking command last spring, Brigadier General Yoo led Marines and coalition forces in Helmand and Nimroz provinces while helping to enhance the capability of the Afghan National Security Forces and improve their credibility in the eyes of the Afghan people. His previous tours in Afghanistan offer a perspective from initial efforts in OEF through the most recent concluding actions.

150428-M-YH418-055: STRAIT OF BAB AL-MANDEB (April 28, 2015) - Corporal Michael Connell, left, an anti-tank missileman with Weapons Company, Battalion Landing Team 3rd Battalion, 6th Marine Regiment, 24th Marine Expeditionary Unit, and Mineman 2nd Class Jared Williamson observe ships and terrain as part of a joint small caliber action team during a transit through the Strait of Bab al-Mandeb aboard the USS Sentry (MCM 3), April 28, 2015. The 24th MEU provided additional SCAT capabilities to the USS Sentry during the transit. The 24th MEU is embarked on the ships of the Iwo Jima Amphibious Ready Group and is deployed to maintain regional security in the U.S. 5th Fleet Area of operations. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Todd F. Michalek/Released)

13 August 2015- The Center for Adaptation and Innovation at the Potomac Institute for Policy Studies as part of its U.S. Marine Corps Returning Commander Speaker Series hosted the commanders of the Iwo Jima Amphibious Ready Group (ARG) and the 24th Marine Expeditionary Unit (MEU).

During their seven month deployment across Europe, Africa and the Middle East, Captain Mike McMillan, USN, and Colonel Scott Benedict, USMC, led a Navy-Marine Corps team that embodied the tenets of scalability, flexibility and adaptability.

This ARG/MEU team accomplished a wide range of missions to include: assisting in the evacuation of U.S. citizens from Yemen, providing security detachments to U.S. Navy ships, executing theater security and partnership exercises, and executing sea control operations in the Strait of Bab Al Mandeb between Yemen and Djibouti.

The latter mission is unique due to a shift in employment paradigms called for in this complex maritime operational environment. Demonstrating the true uniqueness and flexibility of the Navy-Marine Corps Team, the ARG supported the traditional MEU missions and the MEU also supported traditional ARG missions. Additionally, during this deployment, the MEU also was employed in support of the ARG in the execution of traditional Navy missions - sea control and maritime security missions. The supporting role that Marines played in the execution of these sea control operations provides a start point to further explore how to construct future naval campaigns at the operational level that employ all elements of the naval forces in various supporting/supported roles in the various phases of a campaign.

Aggregated for only 6 days, the ARG/MEU team spent 97% of their deployment apart executing split operations, which allowed them to operate independently and execute a larger number and wider range of missions. This deployment model is clearly becoming the norm and is indicative of how the forward deployed Naval forces will operate in the future. This “new normal” will place a premium on understanding not only the difference between split versus disaggregated operations and the implications for the exercising of the tactical control of forces (TACON) but also the requirement for each amphibious warship in the ARG to have sufficient C2 systems and bandwidth, as well as organic ISR to successfully execute likely missions.

Operational concept and doctrine gaps are emerging from the execution of split operations and from the paradigm shifts occurring in relation to blue (ARG) in support green (MEU) and now green (MEU) in support of blue (ARG) operations. These gaps highlight the need for Naval leaders to take the necessary steps to develop the operational concepts that will connect strategic ends to tactical mission sets. This requirement comes at an opportune time for the Navy and Marine Corps to join together and reinvigorate the linkages and relationships that enable the conduct of naval maneuver warfare across the full range of military operations.

The Center for Adaptation and Innovation (CAI) identifies and defines new and potentially disruptive defense capabilities. Specifically, the Potomac Institute for Policy Studies established CAI to assist senior defense leaders grappling with the most demanding issues and problems posed by a complex and uncertain security environment.

11 February 2015

11 February 2015

1600 - 1700

In August 2014, the 26th MEU Command Element commanded by Col Fulford, assumed the roles and responsibilities as the Special Purpose Marine Air-Ground Task Force-Crisis Response-Africa (SPMAGTF-CR-AF). It is a rotational force of about 1,200 Marines and Sailors capable of rapid crisis response. SPMAGTF-CR-AF is forward-positioned to rapidly deploy to support missions such as embassy reinforcement and tactical recovery of aircraft and personnel (TRAP), as well as limited foreign humanitarian assistance and disaster relief operations. Going forward, the unit will have the capability to perform limited offensive/defensive and security operations as required. SPMAGTF-CR-AF can also act as a quick-reaction force (QRF).